We’ve all been there: I make a mistake, bump into someone, or say something hurtful. The natural response? An apology. “I am sorry. Please forgive me.”

But have you ever stopped to consider whether your apology empowers the recipient, or if some apologies, under the guise of remorse (“I am sorry”) and reconciliation (“Please forgive me”), are actually a sneaky form of aggression?

Table of contents

The Power of “I” Statements

People who don’t think shouldn’t talk.

Lewis Carroll, 1832 – 1898

We all know that “close the door”, or “turn off the lights”, or even the cute question “can you please write the report?” are directive statements. Simple English sentences are composed of “subject-verb-object” components. The subject in each of these statements is “You”, as in “YOU close the door”, and “YOU turn off the lights”, and “YOU write the report.” It is easy to see the aggression in “YOU turn off the lights!”, with the dastardly capital letters and exclamation points, while it is a little easier to deny aggression when adding a plea of “you please turn off the lights”. It is still there.

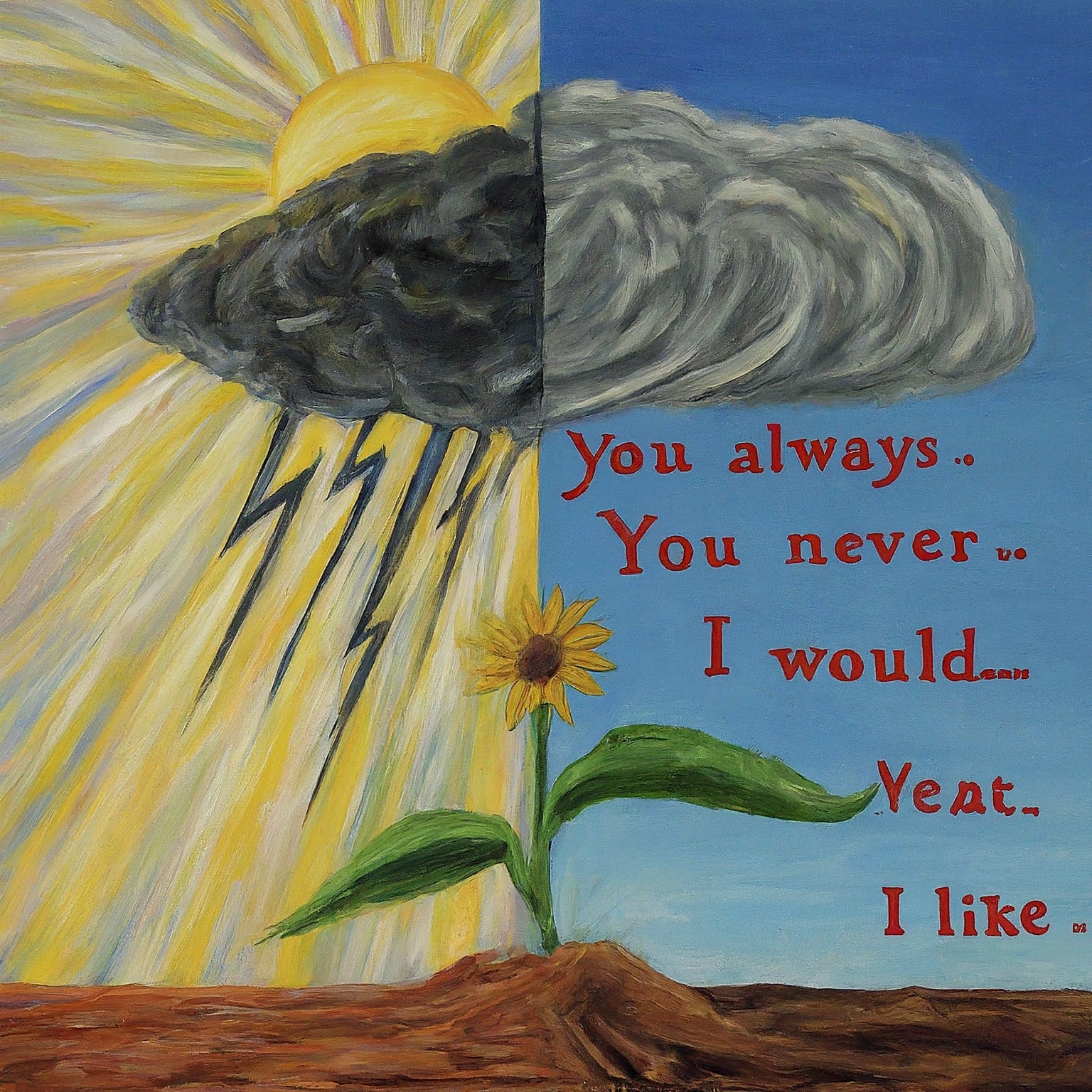

But then the discord comes. “This is how we speak in this country, in this community, in this house. I say I’m sorry, and I expect the other person to listen to me and forgive me.” How does one get beyond these aggressions and micro aggressions?

The “Please Forgive Me” Paradox

I am sorry, please forgive me, thank you, let’s move on.

Ho’oponopono

In working towards harmony, while “I am sorry” acknowledges the mistake, “please forgive me” takes a sharp turn. It subtly transforms the “I am sorry” apology into a “now it is time for you to forgive me” directive. It is all about me being forgiven. The speaker isn’t simply expressing regret; they are actively instructing the listener on how to respond – it is now time for the listener to provide forgiveness to the speaker. Yes, the phrase “provide forgiveness” was intentionally chosen over “offering forgiveness”, because “you forgive me” is directive. You forgive me. Now.

Nonviolent communication (or NVC) argues that seemingly harmless phrases that imply how someone else should act, or telling someone what to do, is aggression. This might sound extreme at first, but reconsider the common apology: “I am sorry. Please forgive me.” Are these two seemingly innocuous sentences harmless?

On the surface, the “I am sorry please forgive me” apology acknowledges wrongdoing and seeks forgiveness and reconciliation. However, “please forgive me” is directive. It places the burden on the other person to take a specific action that you want them to – forgiveness. This disregards the recipient’s emotional process. The other person might not be ready to forgive, they might need to understand why you did what you did, they may have more questions. There may be many more steps to take between “I am sorry” and the eventual “I forgive you” response from the other person. Whether forgiveness ever happens should never be an expectation of your apology. Your apology should stand alone.

Instead of manipulative directives, use “I” statements to communicate your remorse and intentions. “I am committed to doing better” or “I value our relationship” speaks volumes about your commitment to change.

By focusing on empathy and taking accountability, an environment where true forgiveness can blossom. Remember, apologies aren’t about forcing a specific response; they’re about taking ownership, and demonstrating a willingness to rebuild trust. NVC offers a framework to express our needs and concerns authentically, while inviting collaboration and empathy. This shift creates a space for genuine connection and stronger relationships.

The “please forgive me” is no different than another imploring request, “please, now it is time for you to forgive me” – these statements are both aggressive and manipulative. The request puts the burden on the other person to absolve the transgressor, regardless of whether they’re truly ready to do so. It disregards their feelings and the emotional labor required for forgiveness.

A Better Way to Mend Fences

“The only true apology is the one that doesn’t require forgiveness.”

Richelle E. Goodrich

A genuine apology focuses on the recipient situation, not the speaker’s need for absolution, or for “receiving forgiveness”. A sincere apology focuses on taking responsibility and making amends, not necessarily seeking forgiveness. An attitude of apology is, “I am sorry, what can I do in order to make you whole again, what can I do in order to make this relationship whole again? What can I do in order to make you feel comfortable again? What can I do in order to gain your trust again?” It is a humbling shift in mindset to place all the power into the other soul.

What are the components of an empowering apology? NVC suggests creating a restorative environment, taking ownership for your actions, expressing a willingness to make amends, and open the door for a genuine conversation towards rebuilding trust.

- Understand exactly what you did: Don’t apologize until you absolutely know what you have done wrong, and you absolutely take full responsibility for what you have done. If you believe there is a shadow of joint responsibility? Then figure out what you did to contribute to that wrong, and focus your apology on what you did. Be specific. For example, “I know my words were hurtful,” or “I know that I abandoned you last night,” or “I know that I ran the red light and caused the accident.”

- Validate their feelings: Acknowledge the impact your actions had on them. For instance, “My words were crass, inappropriate, and not even true,” or “I know I made you feel that this relationship is not a priority in my life,” or “I know that this accident messed up your vehicle and made you late to work.”

- Take full responsibility: Don’t make excuses or downplay what happened. Own your mistake. “There’s no excuse for what I did. I was wrong.”

- The power of pause: Pause. Stop. Listen. Even if the other person isn’t speaking, stop and listen. Let the other person process what is going on, and what you are saying. If you can’t figure it out for yourself what the other person needs, which you likely cannot since you’ve already made a hardship against them, allow them space to process all that is going on. This is a new situation that has arrived, for both of you. If you made it to “I am sorry”, then let the other person process that statement, because you likely argued a lot leading up to this new apology.

- Offer to make amends: Accept and provide genuine willingness to repair the damage. This may involve a sincere and vulnerable conversation, a thoughtful gesture, or simply giving them space if that’s what they need. Even admitting, “I do not know how to repair what I did, how to make you whole, but I am willing to hear what you need.”

This approach focuses on the impact of our actions and avoids pressuring the other person into a specific response. It allows them the space to process their emotions and choose forgiveness when they are ready, on their timeline, not on ours.

Final thoughts

The only true apology is the one that leads to a change of behavior.

Wayne Dyer, 1940 – 2015

Forgiveness is the other person’s journey, not your journey as the wrongdoer. NVC encourages us to prioritize understanding and empathy over controlling the other person’s response.

The next time you find yourself apologizing, take a moment to reflect. Are you really sorry? Is whatever you are about to apologize for something that you take full responsibility for? Is whatever you are about to say a sincere expression of remorse, or a veiled attempt to get the other person over it, get the other person to accept you, or otherwise control the situation? By recognizing the aggression hidden within “please forgive me,” we can cultivate a world of more authentic apologies and stronger relationships.

Leave a Reply